VEAL STATION

(From The Tale of Two Schools by John W. Nix, printed 1945)

Veal Station was settled in 1852 and in 1858 Capt. W. G. Veal organized it into a community. Captain Veal was a Methodist minister, a leading Mason, and operated a store south of where the school now stands at a place sometimes called Cream Level. Later he moved the store nearer the school building. During the Civil War, he fought on the side of the Confederacy. Veal Station is one of the oldest settlements in Parker County. On January 22, 1867, a post office was established here with Levi Swallow as postmaster, and was continuously in operation until the early part of this century when rural routes were established. The Masonic Lodge operated here from 1860 to 1873. It was known as Eureka Lodge and J. M. Matlock was Worshipful Master. Captain Veal was active in its organization.

Ben W. Akard was teacher of the first school in 1877 and A. R. Swallow, C. C. Knox, and J. L. Campbell were trustees. There were several schools prior to this time of which no record exists. From the very beginning, Veal Station was a school and church center, and prior to the building of the two schools at Springtown, Veal Station had an active college headed by Prof. L. A. Johnson. Written history and tradition make him an outstanding educator, influential, progressive, and learned, and a teacher of the highest standing. The school at Veal Station, which flourished in the 1880’s and 1890’s, was sponsored by the Cumberland Presbyterian Church. Dormitories were built and many houses converted into boarding houses.

From an article printed in the Springtown Pilot and dated July 25, 1884, we learn there was a school taught by a young man in his cabin at Veal Station who styled himself as doctor. His name was not known, but he was facetiously named :Haw Doctor”. In 1854, he taught the first school in this region, if not in Parker County. At about this time Rev. Matthews, a Christian minister, held the first protracted meeting near the old Woody home. It lasted one week and had one convert, a man named McDonald who was first man baptized in the beautiful waters of Ash Creek.

Among the older settlers were, Ben. W., Dr. G. W. and Matt Akard, John Gamble, John Hodge, B. C. and Tom Tarkington, Dr. J. W, Hill, C. C. Culton, C. C. Knox, J. L. Campbell, Benton Lantz, Tom McLaughlin, and the Woody and Swallow families.

(The following was written by Charles Woody & published in The Tale of Two Schools)

Veal Station was settled in 1852 and in 1858 Capt. W. G. Veal organized it into a community. Captain Veal was a Methodist minister, a leading Mason, and operated a store south of where the school now stands at a place sometimes called Cream Level. Later he moved the store nearer the school building. During the Civil War, he fought on the side of the Confederacy. Veal Station is one of the oldest settlements in Parker County. On January 22, 1867, a post office was established here with Levi Swallow as postmaster, and was continuously in operation until the early part of this century when rural routes were established. The Masonic Lodge operated here from 1860 to 1873. It was known as Eureka Lodge and J. M. Matlock was Worshipful Master. Captain Veal was active in its organization.

Ben W. Akard was teacher of the first school in 1877 and A. R. Swallow, C. C. Knox, and J. L. Campbell were trustees. There were several schools prior to this time of which no record exists. From the very beginning, Veal Station was a school and church center, and prior to the building of the two schools at Springtown, Veal Station had an active college headed by Prof. L. A. Johnson. Written history and tradition make him an outstanding educator, influential, progressive, and learned, and a teacher of the highest standing. The school at Veal Station, which flourished in the 1880’s and 1890’s, was sponsored by the Cumberland Presbyterian Church. Dormitories were built and many houses converted into boarding houses.

From an article printed in the Springtown Pilot and dated July 25, 1884, we learn there was a school taught by a young man in his cabin at Veal Station who styled himself as doctor. His name was not known, but he was facetiously named :Haw Doctor”. In 1854, he taught the first school in this region, if not in Parker County. At about this time Rev. Matthews, a Christian minister, held the first protracted meeting near the old Woody home. It lasted one week and had one convert, a man named McDonald who was first man baptized in the beautiful waters of Ash Creek.

Among the older settlers were, Ben. W., Dr. G. W. and Matt Akard, John Gamble, John Hodge, B. C. and Tom Tarkington, Dr. J. W, Hill, C. C. Culton, C. C. Knox, J. L. Campbell, Benton Lantz, Tom McLaughlin, and the Woody and Swallow families.

(The following was written by Charles Woody & published in The Tale of Two Schools)

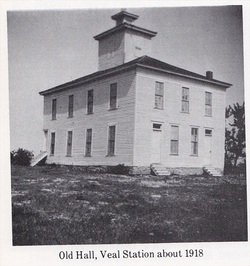

In 1858 a few persons constructed what is now called a community house. The pioneers called it a “Meeting House”. It was the schoolhouse, the church house, and the town hall, without a town. The upper story was occupied as a Masonic Hall. It was constructed upon the hills of the “Great Divide” between the branches of the Trinity River and looked down on a valley in a bend of Walnut Creek, whose waters were as clear as crystal and have never run dry. Its banks were clustered with walnut trees, which provided walnuts with a rare flavor. The creek at Veal Station in pioneer days was known far and wide as the place to camp where one could take a bath and wash his clothes. The first pioneers settled here because there was lasting wood and water.

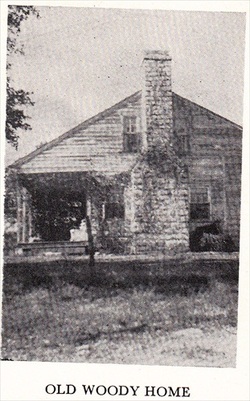

The buildings looked down on the Woody farm in the bend of the creek. They called him Old Bill Woody and he migrated to Texas from the hills of Tennessee in 1846, when he heard it was to become a state of the union, so it is written on his wife’s tombstone in a little graveyard in the corner of what he called his field. They called him Old Bill because he had been here a long time when most of the pioneers arrived and because he was a physical giant and was known far and near for his strength and character. The huge oak logs with which he built his barn are still intact and the tradition is that he built his barn alone and his only boss was his wife.

The old school building was constructed of lumber brought 200 miles from a sawmill in East Texas. Old Bill, with his ox teams and those of his relatives and all his neighbors, crossed the muddy black lands and hauled the lumber which built the two story meeting, which stood there until recently when it was destroyed by fire. Every board in this building was planed by hand and there were no rough surfaces inside or outside. It was painted white and for many decades stood with hardly a board showing decay, and it makes us wonder how he did it.

About this time, perhaps sooner, Bill built him a house across Walnut Creek, which at that time was a mansion. He also hauled the lumber with ox teams 200 miles and planed every board by hand and the house now stands in a cluster of live oak trees. These four rooms ceiled inside with the ceiling lumber planed and grooved by hand by Bill and his son, with a sun porch on the south and large feather beds within made it inviting to sojourners who could form the acquaintance of Bill. Capt. W. J. Veal, for whom Veal Station was named, always made it his stopping place when he preached at Veal Station. Bill’s children and his grandchildren learned their first stories of the Bible from Veal and he was often seen on this little porch telling Bible stories that they never forgot.

Captain Veal continued to preach until the Civil War broke out when he volunteered and went to war. The pioneers of Texas who owned farms and ranches were not permitted to go to war as they were living on what was called a frontier; they were required to stay at home and keep the Indians from invading the more eastern portion of the state, which had been settled first. When the war was over he returned to his work and continued to hold periodical meetings at Veal Station. He was Presiding Elder in 1867.

In the early 1870’s, one night while at what we called a protracted meeting, the word came that the Indians were raiding the country. The women and children going in each direction were loaded in wagons and the young men on horseback, armed. Rode in front and rear and saw each family safely home. The next morning men armed with rifles went in search of the Indians. In this search they found that one of their congregation by the name of Joe Hemphill, going in the direction of Weatherford across the prairie, was scalped and killed by the Indians as he was leaving the church, and Hemphill’s body now rests on the brow of the hill about one mile from where he worshipped. This was the last Indian raid in Parker County and poor Hemphill paid the last of the Indians with his blood. No stone marks the resting place of this pioneer.

This building was always used as a schoolhouse. It is said that one of the teachers of the school whipped one of Bill’s boys so hard that the boy jerked loose from the teacher’s hand and ran home. Bill saw him running away from school and asked why he was out of school. The boy said that he was away from school because the teacher whipped him so hard he was afraid he would kill him. Old Bill took him by the hand, led him up to the schoolhouse and said, “Here he is, teacher; lick him again.” This son always said that while his father could neither read or write, he certainly believed in education. It is strange, indeed, that these rugged men were the men who caused millions of acres of the wild lands of Texas to be set aside and dedicated to the support of the common schools and of the various higher institutions of learning of Texas.

Years went by and Captain Veal preached to larger congregations, some of them were city folk in Dallas and Fort Worth, but he often came back to Veal Station where his career started. He was very active in Masonic work and helped organize many lodges in Texas. In the meantime the pioneers’ fields had been tilled, orchards had been planted, and rich harvests gathered, and some had wines in their cellars.

In 1892 the Confederate Reunion of Texas was convened in Dallas, where the Dallas Fair was in full swing. Captain Veal was its presiding officer; his pictures where in the papers and his prominence at this convention was heralded throughout the state and nation. While presiding at a meeting of Confederate Veterans, in what was known as the Gaston Building, a man well known in Dallas as Doctor Jones walked along the side of the building, slipped up to the side door, drew his revolver, pointed it at Veal’s head, fired and shot him in the temple. Veal’s head fell on the desk in front of him where he was presiding; he was dead. He never spoke again. The meeting was thrown into a panic; Jones surrendered to the Dallas officers and it is well that he did or Veal’s Confederate comrades, with whom he was very popular, would have lynched him.

Dr. Jones was immediately indicted for murder. The Dallas papers and papers throughout the country were covered with the account of this tragic killing. After a time the excitement subsided and Jones was tried and convicted of first degree murder and received a sentence for life in the penitentiary. The case was appealed to the Criminal Court of Appeals in Texas and was reversed.

Captain Veal continued to preach until the Civil War broke out when he volunteered and went to war. The pioneers of Texas who owned farms and ranches were not permitted to go to war as they were living on what was called a frontier; they were required to stay at home and keep the Indians from invading the more eastern portion of the state, which had been settled first. When the war was over he returned to his work and continued to hold periodical meetings at Veal Station. He was Presiding Elder in 1867.

In the early 1870’s, one night while at what we called a protracted meeting, the word came that the Indians were raiding the country. The women and children going in each direction were loaded in wagons and the young men on horseback, armed. Rode in front and rear and saw each family safely home. The next morning men armed with rifles went in search of the Indians. In this search they found that one of their congregation by the name of Joe Hemphill, going in the direction of Weatherford across the prairie, was scalped and killed by the Indians as he was leaving the church, and Hemphill’s body now rests on the brow of the hill about one mile from where he worshipped. This was the last Indian raid in Parker County and poor Hemphill paid the last of the Indians with his blood. No stone marks the resting place of this pioneer.

This building was always used as a schoolhouse. It is said that one of the teachers of the school whipped one of Bill’s boys so hard that the boy jerked loose from the teacher’s hand and ran home. Bill saw him running away from school and asked why he was out of school. The boy said that he was away from school because the teacher whipped him so hard he was afraid he would kill him. Old Bill took him by the hand, led him up to the schoolhouse and said, “Here he is, teacher; lick him again.” This son always said that while his father could neither read or write, he certainly believed in education. It is strange, indeed, that these rugged men were the men who caused millions of acres of the wild lands of Texas to be set aside and dedicated to the support of the common schools and of the various higher institutions of learning of Texas.

Years went by and Captain Veal preached to larger congregations, some of them were city folk in Dallas and Fort Worth, but he often came back to Veal Station where his career started. He was very active in Masonic work and helped organize many lodges in Texas. In the meantime the pioneers’ fields had been tilled, orchards had been planted, and rich harvests gathered, and some had wines in their cellars.

In 1892 the Confederate Reunion of Texas was convened in Dallas, where the Dallas Fair was in full swing. Captain Veal was its presiding officer; his pictures where in the papers and his prominence at this convention was heralded throughout the state and nation. While presiding at a meeting of Confederate Veterans, in what was known as the Gaston Building, a man well known in Dallas as Doctor Jones walked along the side of the building, slipped up to the side door, drew his revolver, pointed it at Veal’s head, fired and shot him in the temple. Veal’s head fell on the desk in front of him where he was presiding; he was dead. He never spoke again. The meeting was thrown into a panic; Jones surrendered to the Dallas officers and it is well that he did or Veal’s Confederate comrades, with whom he was very popular, would have lynched him.

Dr. Jones was immediately indicted for murder. The Dallas papers and papers throughout the country were covered with the account of this tragic killing. After a time the excitement subsided and Jones was tried and convicted of first degree murder and received a sentence for life in the penitentiary. The case was appealed to the Criminal Court of Appeals in Texas and was reversed.

In 1897 the second trial of Dr. Jones came up. It happened that the oldest grandson of Bill Woody, Charles L. Woody, now of New York, was the assistant county attorney of Dallas County and was in charge of the prosecution. A duty to be performed on the one hand, a life-long friendship, a great personal admiration, a devotion almost parental on the other. A choice was made and the prosecution was not only thorough but also brilliant and attracted widespread attention. Bill’s grandson opened the case to the jury and the men in the courtroom said he controlled his wrath and addressed himself to the law and facts. He did well. The jury gave Dr. Jones 20 years in the penitentiary. Again the case was appealed and again reversed and the defendant Jones many years thereafter was tried and convicted of manslaughter, sentenced for two years in the penitentiary and served his term.

It was hard for Veal’s friends and comrades to believe that justice had prevailed, but many said that Jones was given the benefit of the reasonable doubt and he paid the penalty that the statute of Texas had enacted to punish the avenging of insults to its women.

To quote Charles L. Woody: “On December 19, 1935, in passing I noticed that the steeple on the Meeting House, where the first church bell in Parker County rang, was gone. I could not resist stopping. I walked up the steps into the Meeting House, down the aisle to where my father, my grandfather, and my great grandfather had worshipped and listened to the words of Veal. I looked at the little alter that still stood, scarred and worn, and I said to myself, ‘Veal didn’t assault Mr. Jones.’ I turned and walked down to the brow of the hill and looked down upon the graves of William and Elizabeth Woody and said, ‘There is one thing I am certain of, that, if Bill and his wife could rise from their graves, they would say that Veal didn’t do it.’ I stepped into the car, slammed the door and said, ‘Let’s go joe, and returned to New York.”

Veal Station was settled in 1852. A school was established in 1858 by William G. Veal (1831-1891) one of the most prominent men of his time in Texas. The school functioned for more than a half century. William G. Veal was also a very active Mason and organized Masonic Lodges over much of Northern Texas. He was a leading spirit and active in all public improvements.

THE FAMOUS OLD BELL STOLEN

(The following article was from the Weatherford Democrat, March 17, 1917)

Springtown, Texas, March 15, 1917 – The people of Veal Station and all the old-timers of this part of Parker County are very much incensed over the disappearance of the famous old bell that has so long done duty at Veal Station.

Some time during the past few days this deep-toned old relic was stolen from the belfry of the large old school building and there is no information as to the identity of the thieves.

Since the disappearance of the old bell it has been revealed that elaborate preparation had been made for the theft. The thieves constructed strong ladders as a means of reaching the belfry, and the bell was lowered by block and tackle.

The stolen bell was a very large one, weighing approximately one ton, and was composed of bronze or brass, which rendered it very valuable at this time, owing to the high price of all metal. But it was a priceless relic of this section – one of the most valuable possessions of the people of north Parker County, and was perhaps the oldest bell in the portion of Texas.

The bell was brought from Galveston in about 1880, making the long journey from the Gulf coast in an ox wagon, when the first lumber was being hauled to build the original school building at Veal Station, and was at that time a very old bell, having done service on a steamship for an unknown number of years.

The earlier history of the old bell is not known, but for more than a half century it has been an interesting relic and an object of veneration of the citizens residing in northern Parker County and its disappearance has evoked a perfect storm of indignation.

A liberal reward is offered fro the return of the bell or the apprehension of the thieves.

This bell was bought primarily to give warnings of Indian uprisings. When the school was built it was installed in the building, although it was much too large for ordinary school or church purposes. It warned the settlers of the Indians for many miles around; its deep-toned voice called the children of the pioneers to their classes; it called the pioneers to their worship in the church on top of the hill, to the Sunday school, the singings, and the festivals. It rang out the joy of the weddings, it tolled out the funeral dirge of the old timers, as they, one by one, for 65 years, were borne with loving care, by relatives and sorrowing friends down the winding, woodland road to the place, the last place of earthly rest – to await, we believe, the clarion call of greater bells to mansions on High

It was hard for Veal’s friends and comrades to believe that justice had prevailed, but many said that Jones was given the benefit of the reasonable doubt and he paid the penalty that the statute of Texas had enacted to punish the avenging of insults to its women.

To quote Charles L. Woody: “On December 19, 1935, in passing I noticed that the steeple on the Meeting House, where the first church bell in Parker County rang, was gone. I could not resist stopping. I walked up the steps into the Meeting House, down the aisle to where my father, my grandfather, and my great grandfather had worshipped and listened to the words of Veal. I looked at the little alter that still stood, scarred and worn, and I said to myself, ‘Veal didn’t assault Mr. Jones.’ I turned and walked down to the brow of the hill and looked down upon the graves of William and Elizabeth Woody and said, ‘There is one thing I am certain of, that, if Bill and his wife could rise from their graves, they would say that Veal didn’t do it.’ I stepped into the car, slammed the door and said, ‘Let’s go joe, and returned to New York.”

Veal Station was settled in 1852. A school was established in 1858 by William G. Veal (1831-1891) one of the most prominent men of his time in Texas. The school functioned for more than a half century. William G. Veal was also a very active Mason and organized Masonic Lodges over much of Northern Texas. He was a leading spirit and active in all public improvements.

THE FAMOUS OLD BELL STOLEN

(The following article was from the Weatherford Democrat, March 17, 1917)

Springtown, Texas, March 15, 1917 – The people of Veal Station and all the old-timers of this part of Parker County are very much incensed over the disappearance of the famous old bell that has so long done duty at Veal Station.

Some time during the past few days this deep-toned old relic was stolen from the belfry of the large old school building and there is no information as to the identity of the thieves.

Since the disappearance of the old bell it has been revealed that elaborate preparation had been made for the theft. The thieves constructed strong ladders as a means of reaching the belfry, and the bell was lowered by block and tackle.

The stolen bell was a very large one, weighing approximately one ton, and was composed of bronze or brass, which rendered it very valuable at this time, owing to the high price of all metal. But it was a priceless relic of this section – one of the most valuable possessions of the people of north Parker County, and was perhaps the oldest bell in the portion of Texas.

The bell was brought from Galveston in about 1880, making the long journey from the Gulf coast in an ox wagon, when the first lumber was being hauled to build the original school building at Veal Station, and was at that time a very old bell, having done service on a steamship for an unknown number of years.

The earlier history of the old bell is not known, but for more than a half century it has been an interesting relic and an object of veneration of the citizens residing in northern Parker County and its disappearance has evoked a perfect storm of indignation.

A liberal reward is offered fro the return of the bell or the apprehension of the thieves.

This bell was bought primarily to give warnings of Indian uprisings. When the school was built it was installed in the building, although it was much too large for ordinary school or church purposes. It warned the settlers of the Indians for many miles around; its deep-toned voice called the children of the pioneers to their classes; it called the pioneers to their worship in the church on top of the hill, to the Sunday school, the singings, and the festivals. It rang out the joy of the weddings, it tolled out the funeral dirge of the old timers, as they, one by one, for 65 years, were borne with loving care, by relatives and sorrowing friends down the winding, woodland road to the place, the last place of earthly rest – to await, we believe, the clarion call of greater bells to mansions on High