JESSIE MARGARET (MCANALLY) CUMMING

Birth: 3 Nov 1890

Death: 22 Sep 1984

(age 93 years, 10 months, 19 days)

Jessie Margaret (McAnally) Cumming

Jessie Margaret (McAnally) Cumming

Jessie McAnally Cumming was a third generation Parker County native. Her grandparents came to Texas before the Civil War to settle in what was then the edge of Texas frontier ̶ a wild, sparse and impartially brutal country inhabited by a few settlers and raiding Comanche Indians. From these ancestors she inherited fortitude for enduring life’s hardships and a genetic code that would enable her to live to the age of 94 despite numerous afflictions. She witnessed most of the 20th century from the horse and buggy to the jet plane and all the events and innovations in between.

Called Jessie or “Aunt Jessie” by her friends and relatives, she was always “Memaw” to her grandchildren. Like “Judge” or “Reverend”, “Memaw” was an appellation best describing a person whose maternal instincts spread in an oceanic wave to embrace not only her family, but most everyone she knew. Patient, kind and trusting to a fault, Memaw’s life was a testament in helping others. Many times upon arriving at her house, I would find her consoling a neighbor, friend or relative. As the suppliant unfolded a tale of woe, Memaw would listen with that particular quality that today’s psychologists describe as “being present” — a reassuring, understanding without advice or remonstration. On those occasions, I would be instantly jealous – I felt this person was drinking from my emotional fountain. I didn’t realize she had an inner wellspring that never ran dry when people turned to her. Her religious faith and life experiences together forged a pathos that knew no bounds.

Called Jessie or “Aunt Jessie” by her friends and relatives, she was always “Memaw” to her grandchildren. Like “Judge” or “Reverend”, “Memaw” was an appellation best describing a person whose maternal instincts spread in an oceanic wave to embrace not only her family, but most everyone she knew. Patient, kind and trusting to a fault, Memaw’s life was a testament in helping others. Many times upon arriving at her house, I would find her consoling a neighbor, friend or relative. As the suppliant unfolded a tale of woe, Memaw would listen with that particular quality that today’s psychologists describe as “being present” — a reassuring, understanding without advice or remonstration. On those occasions, I would be instantly jealous – I felt this person was drinking from my emotional fountain. I didn’t realize she had an inner wellspring that never ran dry when people turned to her. Her religious faith and life experiences together forged a pathos that knew no bounds.

Sam & Jessie

Sam & Jessie

Memaw was no stranger to suffering. Her husband, Sam, died in 1940, followed by her two sons, Herbert first and then Bob, in World War II (plaques to their wartime service are on the entry to Clark Cemetery — another story), and the last surviving son, Richard Alton, my Dad, in 1961. These and other hardships she suffered might make a person bitter or cynical toward life and religion. Or, the opposite, a religious zealot. Not her. She was the most religious person I’ve ever met in the truest sense of the word – committed to God despite what life brought her.

Unlike prison converts and the professional religionists on TV, to “believe” in God did not automatically punch a ticket into heaven in Memaw’s ethos. I think her attitude toward salvation could be summed up; as “God believing in you, is more important than you believing in him.”

Unlike prison converts and the professional religionists on TV, to “believe” in God did not automatically punch a ticket into heaven in Memaw’s ethos. I think her attitude toward salvation could be summed up; as “God believing in you, is more important than you believing in him.”

Jessie

Jessie

In retrospect, she was an expert in what I would call “embracing of doubt” – a lost skill in today’s culture. No pat answers; no platitudes. No high-handed proselytizing other people to assuage existential angst – just simple trusting that transcended mental machinations. When I would ask her what would become of us if the Atom Bomb hit us (remember the 1950s?), she would answer, “I don’t know, but I figure God knows more than we do.” On the surface of it, I thought this was a lame answer, but a spiritual animus radiated from her that one could almost feel. It made me ask myself “Does she really know God?”

On the temporal plane, Clark Cemetery was holy ground to Memaw. On a hot summer afternoon in the 1960s, she dragged my brother and me out to Clark. It was a rare treat for Memaw to make the 10-plus mile sojourn from her home in Weatherford to the cemetery because she never learned to drive a car. Her solo attempt in the 1940s ended in a fender-bender that convinced her she lacked the coordination to operate an automobile. I’m not exactly sure how we got to the cemetery, but it was probably with “the Glenns”, a polite but laconic couple whose conversational skills as a comparison would make Sitting Bull look like Rodney Dangerfield. Mr. Glenn, who always dressed in a Dove gray suit, would open the back door of his Dove-gray old Packard and we would all pile into the Dove-gray upholstered backseat. We then proceeded at a snail’s pace on a trip bereft of color (Dove gray) or conversation.

On the temporal plane, Clark Cemetery was holy ground to Memaw. On a hot summer afternoon in the 1960s, she dragged my brother and me out to Clark. It was a rare treat for Memaw to make the 10-plus mile sojourn from her home in Weatherford to the cemetery because she never learned to drive a car. Her solo attempt in the 1940s ended in a fender-bender that convinced her she lacked the coordination to operate an automobile. I’m not exactly sure how we got to the cemetery, but it was probably with “the Glenns”, a polite but laconic couple whose conversational skills as a comparison would make Sitting Bull look like Rodney Dangerfield. Mr. Glenn, who always dressed in a Dove gray suit, would open the back door of his Dove-gray old Packard and we would all pile into the Dove-gray upholstered backseat. We then proceeded at a snail’s pace on a trip bereft of color (Dove gray) or conversation.

Sam & Jessie

Sam & Jessie

That afternoon, grandmother and grandsons walked around the cemetery as Memaw unfolded stories about friends and relatives. I could kick myself now for not taking mental notes from her rich, descriptive, oral history. Clark Cemetery was her anchor to the past and she cared deeply for it, devoting her time and what little spare money she had to support this small community cemetery.

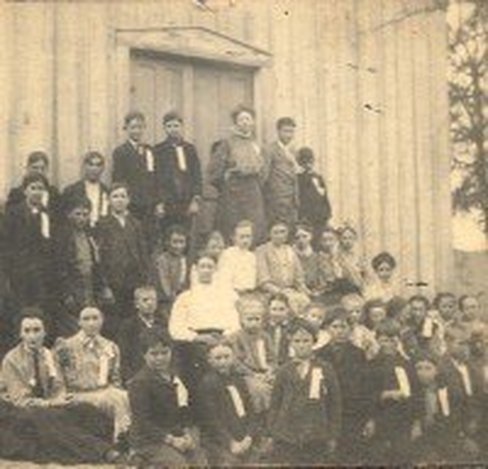

Though a dedicated and loved one-room school teacher in her early years, Memaw always lamented that she couldn’t fulfill her

childhood dream of becoming a “Missionary” – an ambition probably stemming from her Methodist upbringing and the evangelical tenants of John Wesley. But she was a true missionary and didn’t know it. To illustrate, years after her death, I was in an elderly couple’s Weatherford home attempting to get them to sign an Oil and Gas Lease for a property they owned in Parker County. The husband and I thrashed out details and told each other oilfield “war stories” as his wife sat passively across the room. Disinterested, distracted she looked totally depressed and lifeless. It appeared to me some terrible tragedy had struck her. Finally the conversation got to the husband asking, “Who are you and where are you from?” I began reciting my Curriculum Vitae and mentioned Mrs. Jessie Cumming, a longtime Parker County resident was my grandmother. The wife jumped like she had stuck her finger in a light socket. Suddenly a beatific smile came over her and you could tell she was retracing memories. She began regaling us both with stories about Memaw and how much she was blessed by knowing her. I didn’t get the lease, but I realized how Memaw was a true Missionary.

Jessie Margaret (McAnally) Cumming and her husband, Samuel Eugene Cumming are interred and their sons Herbert and Bob are memorialized at Clark Cemetery. Their spirits live on.

Written by Dwight Cumming (grandson of Jessie Cumming)

Photos courtesy of Dave Cumming (grandson of Jessie Cumming)

Though a dedicated and loved one-room school teacher in her early years, Memaw always lamented that she couldn’t fulfill her

childhood dream of becoming a “Missionary” – an ambition probably stemming from her Methodist upbringing and the evangelical tenants of John Wesley. But she was a true missionary and didn’t know it. To illustrate, years after her death, I was in an elderly couple’s Weatherford home attempting to get them to sign an Oil and Gas Lease for a property they owned in Parker County. The husband and I thrashed out details and told each other oilfield “war stories” as his wife sat passively across the room. Disinterested, distracted she looked totally depressed and lifeless. It appeared to me some terrible tragedy had struck her. Finally the conversation got to the husband asking, “Who are you and where are you from?” I began reciting my Curriculum Vitae and mentioned Mrs. Jessie Cumming, a longtime Parker County resident was my grandmother. The wife jumped like she had stuck her finger in a light socket. Suddenly a beatific smile came over her and you could tell she was retracing memories. She began regaling us both with stories about Memaw and how much she was blessed by knowing her. I didn’t get the lease, but I realized how Memaw was a true Missionary.

Jessie Margaret (McAnally) Cumming and her husband, Samuel Eugene Cumming are interred and their sons Herbert and Bob are memorialized at Clark Cemetery. Their spirits live on.

Written by Dwight Cumming (grandson of Jessie Cumming)

Photos courtesy of Dave Cumming (grandson of Jessie Cumming)