Carter, Texas

A decaying old schoolhouse, a crumbling piano in the tabernacle and a few markers transcribed with some of the history are all that remain of the town of Carter. Located just off of highway 51 North, a few miles northwest of Clark Cemetery, Cartersville was founded in 1866 and named in honor of Judge W. F. Carter. It was originally called Carterville but was changed to Carter on January 23, 1888.

Like other communities in north Parker County, the history of Carter overlaps with the history of Clark Cemetery. In fact, many of the people listed as having lived in and around Carter are buried in Clark Cemetery. Some of those families included are George Alexander Clark, Isaac Crelia, and various members of the Dobbs, Green, and Tackett families.

Like other communities in north Parker County, the history of Carter overlaps with the history of Clark Cemetery. In fact, many of the people listed as having lived in and around Carter are buried in Clark Cemetery. Some of those families included are George Alexander Clark, Isaac Crelia, and various members of the Dobbs, Green, and Tackett families.

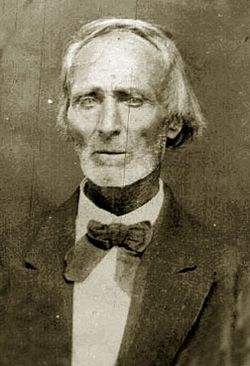

Rev. Pleasant Tackett

Rev. Pleasant Tackett

One of the first settlers of Parker County was Rev. James Pleasant “Ples” Tackett (great grandfather of George William Tackett-buried at Clark Cemetery). Rev Tackett was born in Kentucky on April 22, 1803. He was a natural leader and led the way for fifteen families seeking a new place to settle. They arrived in Parker County, just north of Carter, in 1854. There were no roads or bridges and recent rain had made the Clear Fork impassable so they camped on its banks where at night they gathered around camp fires, sang old time songs and Mr. Tackett preached. He also visited other camps and preached. On one of these trips the Indians pursued him. He was riding a mule and in the chase he was shot in the foot with an arrow. Without dismounting, he reached down and pulled the arrow out and used it as a lash to increase speed of the mule.

The Clear Fork finally receded and the settlers selected and staked out locations and began building homes and development of a new country, facing the hardships and inconveniences of a far-out frontier. Being in a new wilderness often meant settlers were on their own as far as medical care. Shortly after arriving, the Pleasant Tackett family, eleven in number, which included three orphan children named Lee, drove their wagons to a valley at the head of Walnut Creek as the selected location, where the preacher and his boys began at once the building of log houses, with dirt floors, and called it home.

Maggie Lee, the oldest of the orphans, and the family favorite, while moving the camp bedding, was bitten by a huge rattlesnake which was coiled under the bed. It sank its cruel fangs deep into her flesh and drove its deadly venom into her blood from which she died the next day. Imagine the sorrow and sadness as the family dug the first grave in this new unnamed and unorganized county. A concrete monument now marks the lone grave on which is inscribed, “Maggie Lee, the first white person buried in Parker County-I go to prepare a place for you, that where I am, you may be also.”

The Clear Fork finally receded and the settlers selected and staked out locations and began building homes and development of a new country, facing the hardships and inconveniences of a far-out frontier. Being in a new wilderness often meant settlers were on their own as far as medical care. Shortly after arriving, the Pleasant Tackett family, eleven in number, which included three orphan children named Lee, drove their wagons to a valley at the head of Walnut Creek as the selected location, where the preacher and his boys began at once the building of log houses, with dirt floors, and called it home.

Maggie Lee, the oldest of the orphans, and the family favorite, while moving the camp bedding, was bitten by a huge rattlesnake which was coiled under the bed. It sank its cruel fangs deep into her flesh and drove its deadly venom into her blood from which she died the next day. Imagine the sorrow and sadness as the family dug the first grave in this new unnamed and unorganized county. A concrete monument now marks the lone grave on which is inscribed, “Maggie Lee, the first white person buried in Parker County-I go to prepare a place for you, that where I am, you may be also.”

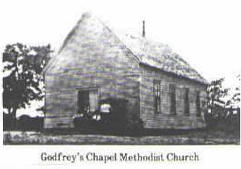

Rev. Tackett was a stockman, teacher, farmer, and a courageous Indian fighter but foremost he was a Methodist minister that enjoyed spreading the word of God. He was a licensed preacher and founded Goshen Church. This overlaps with the history of John W. Godfrey, buried at Clark Cemetery. Godfrey’s Chapel Methodist Church had its beginnings at Goshen. In 1854 John Godfrey joined with Rev. Tackett and other Christian believers and helped establish public services at this pioneer church. Later Rev. Godfrey wanted a church closer to his home. In 1884 he obtained a land donation of 3 acres from James Edward “Jim” and Eliza Ann (Dobbs) Clark and established Godfrey’s Chapel Methodist Church near Clark Cemetery. The church was moved in 1893 to land donated by William M. and Nancy Ann (Mitchell) Dobbs on what is now Upper Denton Road. A monument stands at this site today.

As the settlement around Carter grew and stock accumulated around the homes, the Indians increased their raids in which they killed the settlers, drove off the stock, and robbed the homes. It is estimated that from the first settlements in 1854 to the last raid in 1874, that within a radius of 100 miles-including Parker County, which was the worst sufferer, the Indians stole and destroyed six million dollars’ worth of property, killed and scalped or carried away about 400 people into captivity.

The Tacketts were very active in warding off and fighting back these savage attacks. In one fight, Jim Tackett, one of the boys, was shot in the forehead with an arrow tipped with a steel spike, which drove through his skull and deep into his head. In trying to pull the arrow out he broke it off and left the spike sticking out. There was no doctor or surgical instruments in the county, and the only thing they could find with which to extract the spike was a pair of bullet molds, which was made a little like the pliers of the present day. They found in trying to extract the spike that in entering it had curved the skull in such a way that to pull on it would tighten the bond grip and to forcibly withdraw it would tear open the head bone and result in instant death, so with Divine faith, they let nature take its course. Jim Tackett lived with a rusty steel spike sticking in an inch and a half deep in his skull for eight weeks. By the help of nature the bone slackened its grip on the spike until it was slipped out.

Carter was a fertile land and local springs made it a desirable place for the early pioneers to settle. The springs were known as Indian or Carter Springs. In 1858, Charles Goodnight called them Rock Springs when he built a large stone house for his mother and stepfather near Carter. By the late 1850’s and early 1860’s, besides Rev. Tackett, several other families had also moved into the area. John Vardy, of Cedar Rapids, Iowa, along with his second wife, Amanda Prague, five daughters, and one son, made the journey in a covered wagon. Mr. Vardy was a cabinet maker and carpenter. He built and operated an oxen powered corn mill.

Dr. Robert Montgomery, born in North Carolina, was married in Giles County Tennessee and had one son and three daughters. He married his second wife, Malinda Duff, in Missouri and they had eight children. He served in the Missouri Legislature from 1838-1848. After raising his second family, he moved to Cartersville. He met and married Drucilla Vardy Canafax, widow of Newton Canafax who had died from an illness contracted while serving in the Civil War. Dr. Montgomery was the doctor for the community as well as an outstanding farmer. On March 4, 1871, he was murdered at the front gate to his home. In 1877, the Texas Rangers killed the murderer when he resisted arrest in Wilson County, Texas. Dr. Montgomery is buried in Canafax Cemetery about two miles from Carter.

In August, 1872, several young men who resided at Carter had been attending church at Veal Station and were returning after the night service when they were fired on by Indians who hid in the bushes. The horse that Joseph Hemphill was riding was disabled by a shot and the Indians seized the opportunity and rushed upon the unfortunate young man and brutally murdered him and took his scalp as a trophy. The other men escaped and reported the affair at Veal Station. The Indians were next heard of near Jacksboro with a large drove of horses.

Another Tennessee arrival was Dr. J. W. Barnett. He came to Cartersville with his wife and four children. On August 23, 1875, he represented Parker County at the last Constitutional Convention of Texas.

As the settlement around Carter grew and stock accumulated around the homes, the Indians increased their raids in which they killed the settlers, drove off the stock, and robbed the homes. It is estimated that from the first settlements in 1854 to the last raid in 1874, that within a radius of 100 miles-including Parker County, which was the worst sufferer, the Indians stole and destroyed six million dollars’ worth of property, killed and scalped or carried away about 400 people into captivity.

The Tacketts were very active in warding off and fighting back these savage attacks. In one fight, Jim Tackett, one of the boys, was shot in the forehead with an arrow tipped with a steel spike, which drove through his skull and deep into his head. In trying to pull the arrow out he broke it off and left the spike sticking out. There was no doctor or surgical instruments in the county, and the only thing they could find with which to extract the spike was a pair of bullet molds, which was made a little like the pliers of the present day. They found in trying to extract the spike that in entering it had curved the skull in such a way that to pull on it would tighten the bond grip and to forcibly withdraw it would tear open the head bone and result in instant death, so with Divine faith, they let nature take its course. Jim Tackett lived with a rusty steel spike sticking in an inch and a half deep in his skull for eight weeks. By the help of nature the bone slackened its grip on the spike until it was slipped out.

Carter was a fertile land and local springs made it a desirable place for the early pioneers to settle. The springs were known as Indian or Carter Springs. In 1858, Charles Goodnight called them Rock Springs when he built a large stone house for his mother and stepfather near Carter. By the late 1850’s and early 1860’s, besides Rev. Tackett, several other families had also moved into the area. John Vardy, of Cedar Rapids, Iowa, along with his second wife, Amanda Prague, five daughters, and one son, made the journey in a covered wagon. Mr. Vardy was a cabinet maker and carpenter. He built and operated an oxen powered corn mill.

Dr. Robert Montgomery, born in North Carolina, was married in Giles County Tennessee and had one son and three daughters. He married his second wife, Malinda Duff, in Missouri and they had eight children. He served in the Missouri Legislature from 1838-1848. After raising his second family, he moved to Cartersville. He met and married Drucilla Vardy Canafax, widow of Newton Canafax who had died from an illness contracted while serving in the Civil War. Dr. Montgomery was the doctor for the community as well as an outstanding farmer. On March 4, 1871, he was murdered at the front gate to his home. In 1877, the Texas Rangers killed the murderer when he resisted arrest in Wilson County, Texas. Dr. Montgomery is buried in Canafax Cemetery about two miles from Carter.

In August, 1872, several young men who resided at Carter had been attending church at Veal Station and were returning after the night service when they were fired on by Indians who hid in the bushes. The horse that Joseph Hemphill was riding was disabled by a shot and the Indians seized the opportunity and rushed upon the unfortunate young man and brutally murdered him and took his scalp as a trophy. The other men escaped and reported the affair at Veal Station. The Indians were next heard of near Jacksboro with a large drove of horses.

Another Tennessee arrival was Dr. J. W. Barnett. He came to Cartersville with his wife and four children. On August 23, 1875, he represented Parker County at the last Constitutional Convention of Texas.

Cartersville was founded in 1866 by Judge W. F. Carter, T. Parkinson, and W. C. Vardy. That same year, Judge Carter built the first steam powered mill in the county. The mill was bought for $900 by Thomas Parkinson and moved with oxen and wagon from its location south of Weatherford for $55. In 1867, they enlarged it, and soon after connected a cotton gin to it. The flour manufactured there was regarded with so much favor at the Houston State Fair in 1873 that it was awarded the best flour in the state. In 1891, the mill was destroyed by fire.

Cartersville consisted of two major streets. Main Street extended north and south of the town. Striking off to the west, from the north end of Main Street, was College Avenue. College Avenue ran across Spring Creek and on up to the college site on the hill. The Main Street accommodated three stores – the principal one being run by W. D. Milliken – one blacksmith, and a post office. Furthermore, College Avenue supported a corn mill, a cotton gin, a flour mill and school building along with one half dozen or more modest buildings.

Cartersville consisted of two major streets. Main Street extended north and south of the town. Striking off to the west, from the north end of Main Street, was College Avenue. College Avenue ran across Spring Creek and on up to the college site on the hill. The Main Street accommodated three stores – the principal one being run by W. D. Milliken – one blacksmith, and a post office. Furthermore, College Avenue supported a corn mill, a cotton gin, a flour mill and school building along with one half dozen or more modest buildings.

Theola (Dobbs) Ellis & Lillie Frances Clark

Theola (Dobbs) Ellis & Lillie Frances Clark

In the early 1890’s, the general population of Cartersville stood at approximately seventy-five residents. The young children of Cartersville attended school under the supervision of Mr. Monhann. Teachers at Cartersville included J. R. Fleetwood from 1877 to 1879 and J. W. Simpson. Other teachers were Lillie Frances Clark and Theola (Dobbs) Ellis. (pictured left; photo courtesy of Linda Ralston Reedy)

The U.S. Post Office was established at Cartersville on January 3, 1867. Mr. Henry C. Vardy was the first postmaster. But on February 28, 1907 the Post Office was closed down and moved to Springtown, Texas.

The first Baptist church organized in the county was at the home of Anderson Green, six miles northeast of Weatherford, by Rev. N. T. Byers in July, 1855. This church elected Anderson Green and William May as their first deacons. Anderson Green was the son of a Revolutionary War soldier and many of his descendants are buried in Clark Cemetery, including his son, Alfred M. Green, a Confederate Civil War soldier.

By the early 1900’s, business was beginning to decline for the leading business men of Carter. James Blevins, the blacksmith for the community; William Green, a larger cattle dealer; J. C. Prague, a carpenter and J. H. Tea, the community physician. The stores were starting to close, the post office had already closed, and finally, in April, 1919, the school closed its doors to the youth of Carter. A new school was built to accommodate the students from Central, Union and Carter.

The U.S. Post Office was established at Cartersville on January 3, 1867. Mr. Henry C. Vardy was the first postmaster. But on February 28, 1907 the Post Office was closed down and moved to Springtown, Texas.

The first Baptist church organized in the county was at the home of Anderson Green, six miles northeast of Weatherford, by Rev. N. T. Byers in July, 1855. This church elected Anderson Green and William May as their first deacons. Anderson Green was the son of a Revolutionary War soldier and many of his descendants are buried in Clark Cemetery, including his son, Alfred M. Green, a Confederate Civil War soldier.

By the early 1900’s, business was beginning to decline for the leading business men of Carter. James Blevins, the blacksmith for the community; William Green, a larger cattle dealer; J. C. Prague, a carpenter and J. H. Tea, the community physician. The stores were starting to close, the post office had already closed, and finally, in April, 1919, the school closed its doors to the youth of Carter. A new school was built to accommodate the students from Central, Union and Carter.

underneath the tabernacle (December 2013)

underneath the tabernacle (December 2013)

Today you can walk around Carter reading one of the ten monuments or the Texas Historical marker erected as a reminder of its history. Besides the monuments, the only thing that remains of Carter is the badly decaying old schoolhouse and tabernacle. One can only imagine the once striving community as you walk under the tabernacle with its benches still lined up in rows and the remains of the piano standing at the front.

(adapted from: History of Parker County, 1980, Parker County Historical Commission; The Tale of Two Schools, 1945, John W. Nix; and the Historical narrative written for the Texas Historical marker application)

(adapted from: History of Parker County, 1980, Parker County Historical Commission; The Tale of Two Schools, 1945, John W. Nix; and the Historical narrative written for the Texas Historical marker application)